Reflections and Conversations within

Cities of the Deaf (2021)

Reem Khorshid

category:

Reflective Essay

date:

April 2021

author:

Reem Khorshid

drawings and photo credits:

Reem Khorshid

published by:

Spatial Sound Institute

Reflective Essay

date:

April 2021

author:

Reem Khorshid

drawings and photo credits:

Reem Khorshid

published by:

Spatial Sound Institute

Reem Khorshid, an architect and researcher, shares a personal reflection piece to raise awareness of the different sonic realities that surround us. For her residency at the Spatial Sound Institute, she addresses a set of essential questions for critical inquiry that can help envision urbanism practices for accessible cities and spaces.

The following feature takes a deeper look into Reem's experiences with and discovery of urban sounds after acquiring cochlear implants, as well as how she navigates this new reality, which led to the project “Cities of the Deaf”.

Sound is quite subjective

The plethora of my experiences with urban sounds occurred in cities I grew up in such as my hometown Cairo, or in cities I had previously visited several times before. I could urge that I have vivid sonic memories of particular places and locations, which I now utilize constantly to distinguish between how the world sounded before and after I received cochlear implants in February 2020.

In Cairo, familiar sounds include the placid residential neighbourhood I grew up in, with its muffled breeze and its silent acoustics outside of my room’s window. With the different quality and textures of sound that I am now hearing due to the technicalities of the cochlear implants technology, I find experiencing these spaces with a pair of bionic ears both disorienting and overwhelming; with my visual, tactile and sonic memories contradicting one another.

The emotionally staggering encounter with the new sounds of once familiar places, especially Cairo where I was born and raised, necessitated altering the indexed and stored sound memories to adapt to their new sonic qualities. Cairo was my serene bedroom, entwined with my relentless tinnitus and the sound of my own breathing. With cochlear implants, the old lulled sounds of home clashed with new crisp commotions of the unfamiliar.

Sonic diversity and acoustic ecology are topics that I may have thought of before as an architect, but rarely had the chance to represent in any of my work. However, after getting implanted, the stark transformation in the way I experienced spaces was eye-opening. Not only are urban sounds complex, but I find sound itself to be quite subjective — something that became clearer to me as I interpreted the differences in sound qualities and characteristics before and after receiving cochlear implants. Cities of the Deaf was envisioned particularly and as a result of this incongruous contact. The new sonic realities I was encountering were not only auditory, but also spatial and urban, with the inevitable manifestation and reformation of my own personal mechanisms of spatial navigation and consciousness of my surroundings.

Accessibility and Open-Ended Approaches

Linking the familiarity with architectural and urban subjects and the aural impressions of my everyday experiences unlocked the context to this work — first and foremost in personal and investigative writings on city sounds and urban topographies. Several questions about phonic identity and sonic accessibility in urban planning came up: How can cities and spaces be designed with d/Deaf-centric spatial considerations? How do the deaf and hard of hearing navigate spaces based on its audiovisual characteristics?

Answers to such questions are not limited to sound interpretation; they also necessitate research into wider topics such as human agency and observing political/social behaviours, as well as their relationship to spatiality and visual culture. One can’t ignore that sound and silence are political tools. In fact, it can be considered as vital modes or mechanisms of resistance that are inextricably linked to urban and spatial boundaries. Nevertheless, sound is an element that is often ignored in urban design and city planning, possibly because of its prominence as an intangible medium of political transgression, neglecting its significance as a fundamental urban element that influences spatial and urban accessibility.

Broadly speaking, the topic of accessibility should be addressed with experimental, challenging and open-ended approaches that ensure frequent and up-to-date solutions that fit the constantly changing lived experiences and needs of different communities. Architects, planners and design practitioners unfortunately often approach this discourse as a set of immutable design regulations that don’t take into account the different and autonomous needs of the people who need access. Moreover, design practices nowadays are more focused on addressing issues that identify with environmental design planning, such as visual identity, smart infrastructure development, public transportation and mobility access, often overlooking the accessibility challenges of people with sensorial, mental and intellectual disabilities.

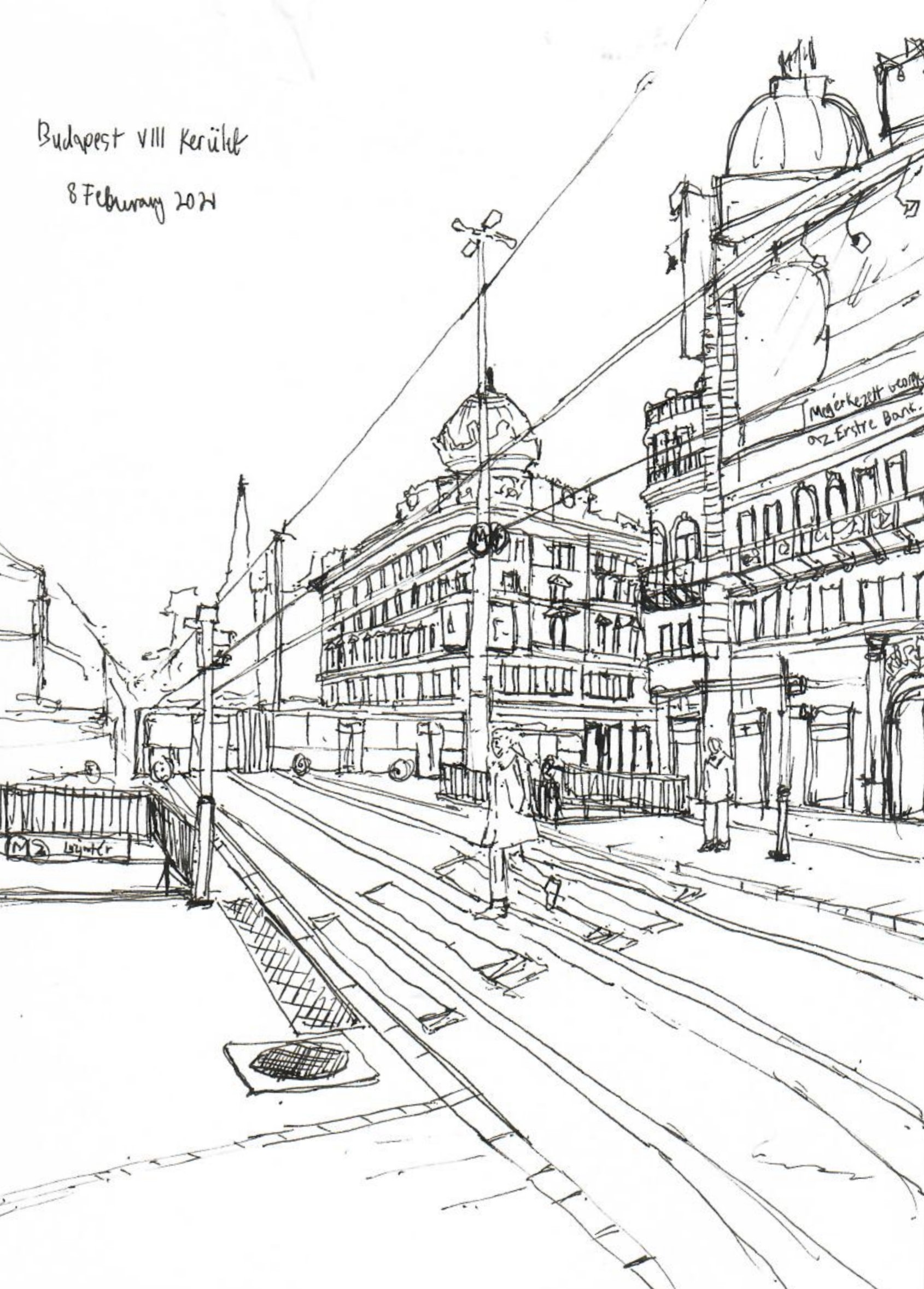

Exploring the urban soundscapes of Budapest

Despite an initial intention to create sound models of Cairo, I decided to choose Budapest as the focus of my sound/urban investigation. In contrast to Cairo, where I have a strong emotional attachment to its spaces and sounds from my childhood, my contact with Budapest’s urban, visual and auditory elements was fairly objective and unprejudiced by nostalgia or memory.

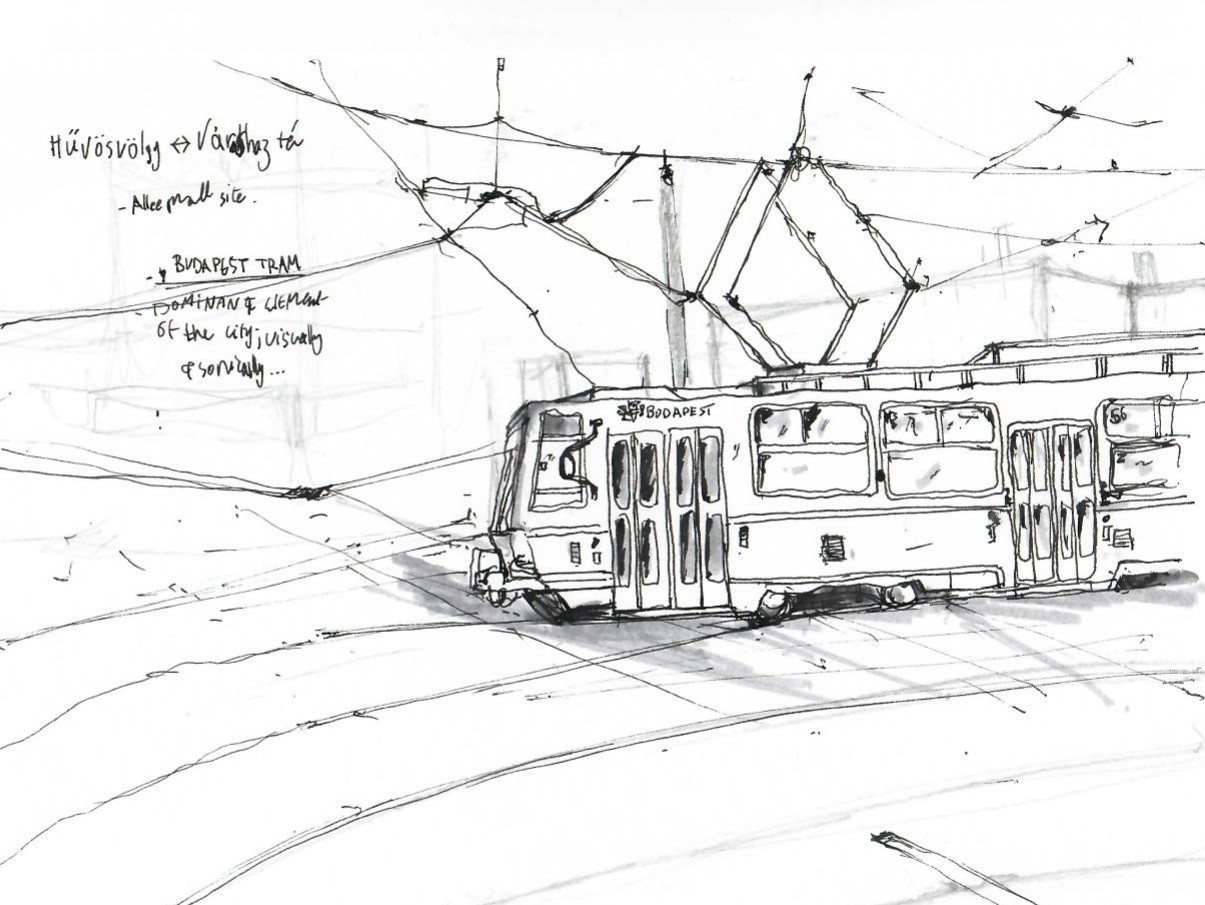

In Budapest, sounds were defined merely by their frequencies, textures and decibels. I spent some time wandering around the city's bustling streets, unbothered but also amused by the city's rich visual and sonic culture. The interminable sounds of moving trams were the first sound to capture my attention in Budapest now that I can hear a much wider spectrum of acoustics, frequencies and pitches. In some respect, the endless sequence of yellow tram carts clamoring along rusted rails seemed alien, possibly because Cairo's tramways had been discontinued a while ago. In Budapest, Tram number 47 became a routine ride out of Budafok and into other sonic timelines to the city center during the residency. Unexpectedly, the more I immersed myself in the cacophony of various soundscapes, the more I thought about silence, not as a setting or a state of ambience but rather as a sound – just as I hear when I switch off the sound processor of my cochlear implants.

Reading about John Cage’s conceptual work 4'33 known as the “silent piece”, I began to think of the subjectiveness of silence as a form of sound absence - the differences between what silence means for the hearing, the d/Deaf and the hard of hearing. In Cage’s composition, 4 '33 was the sound of the environmental ambient of the surroundings as well as mundane, everyday life sounds of the listeners — proving that there is no such thing as silence. However, from a personal perspective as someone who identifies as deaf, silence is rather the mundane reality than an absence of melodic or sonic expectations as contemplated in 4'33. Cage’s work, whether performances of music or rhythmic forms of speech such as Lecture on Nothing are (art) performances. In such a manner, silence becomes an ephemeral communal commodity, shared between the composer, performer and the listeners. Although I have come to agree with Cage’s interpretation that there is no absolute silence, as a deaf person, silence for me is personal, something that I rarely thought of as an urban phenomenon. Only after being implanted and hearing ranges of cacophonies is when I made attempts to materialize silence as a sound rather than a common phenomenon.

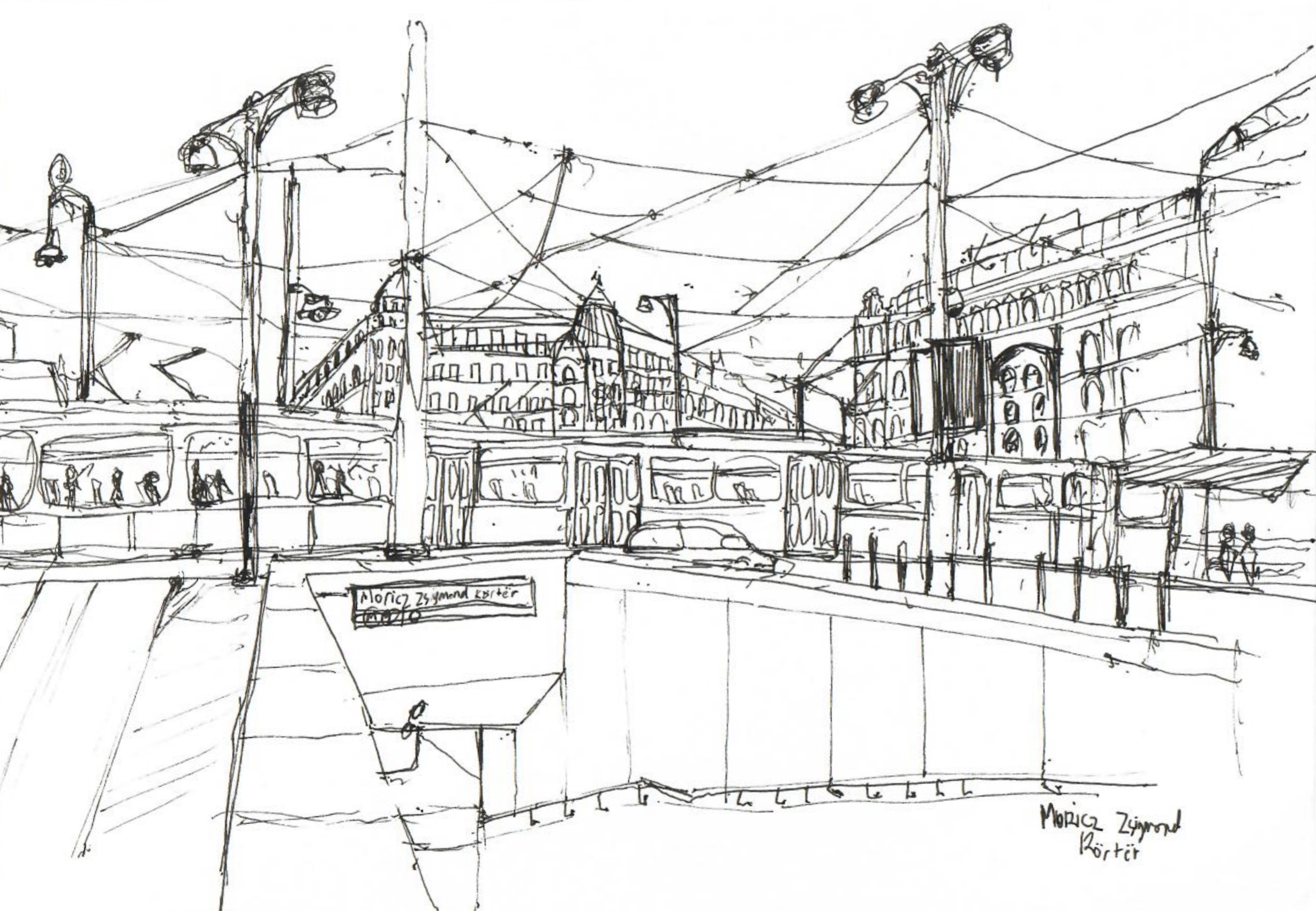

After days of urban exploration, I chose Móricz Zsigmond square as the main terrain for field recordings and inspiration. The intersections, various means of transportation, movement and energy provided a rich amalgamation of sound content. I became intrigued by the concept of manipulating and controlling urban sounds to enhance or alter the perception of spaces, even for the average hearing person. I distinctly paid attention to the notion of sonic perception - with the recognition that auditory perceptions can be subjective, with each average listener, hearing or d/Deaf, perceiving sounds differently. And as a deaf person myself, I wanted to produce sound pieces that represent the various spatial perceptions and perspectives of the hard of hearing and implanted. Field recordings and sound documentation in Budapest consisted of recordings of the sounds of arriving, braking and departing trams, the passing cars and howling ambulances sirens. Furthermore, sounds of human footsteps and conversation chatter were also recorded. A general outdoors ambience was recorded with a Zylia microphone, creating a spatial sonic scene of all the urban sources of sounds. These separate recordings were mixed, composed, edited and amplified to sketch three sonic environments of a hypothetical or imagined public space in Budapest's center.

Raising awareness through three perspectives

The pieces named ear, deaf ear and implanted ear convey the sonic reality as experienced by an ordinary person, a hard of hearing person and an implanted individual. While the ear is created by combining multiple recordings, the deaf ear and implanted ear use the same mixed recordings of the ear, but with different audio effects to recreate the other two peculiar acoustic realities.

The critical exchange and conversations I had with Vladimir Razhev, the technical director at SSI were crucial to the project’s development. Discussions on sound perception as well as examination and experimentation with various frequencies and ranges led to the development of the three models, especially Vlad's contribution to audio verifications.

Creating a sound installation while being deaf is a fascinating assignment where the passive listening process turns into an active act. Attentive and close-listening was required to represent how average listeners and the deaf may navigate streetscapes into the recordings. Another challenge was achieving the desired results and consistency in the implanted ear version of the piece, particularly because I was hearing the ear piece through the implants. As a result, we relied on the numbers and frequency ranges of how my implants' sound processors are programmed to produce the implanted sound piece. It was more of a scientific or technical approach, with numbers taking precedence over manual and organic descriptions of sound perception.

Music Perception

While uncovering and interpreting the different sonic agencies of cities, including the environmental, industrial and man-made sounds, I was curious to investigate sound perception when it comes to music. Personally, I still find it hard to listen to music since I was implanted, especially given that music involves powerful emotional and physiological responses. A lot of the songs and melodies I have always enjoyed do not only sound the same anymore, and in some cases, they don’t sound good at all. Music enjoyment is one of the most advanced stages of cochlear implant rehabilitation, not just because of the exotic musical quality delivered by the implant but also because of the limitations of these technologies in transmitting the full sound spectrum and characteristics of sound. With high-frequency hearing loss as one of the most common types of hearing loss, it means that only low frequency and pitch bass instruments are audible. On the other hand, music perception is more complex and challenging through an auditory implant. The poor frequency resolution of cochlear implants diminishes several components of music, such as the pitches of vocals and instruments as well as the quality and timbre of sounds.

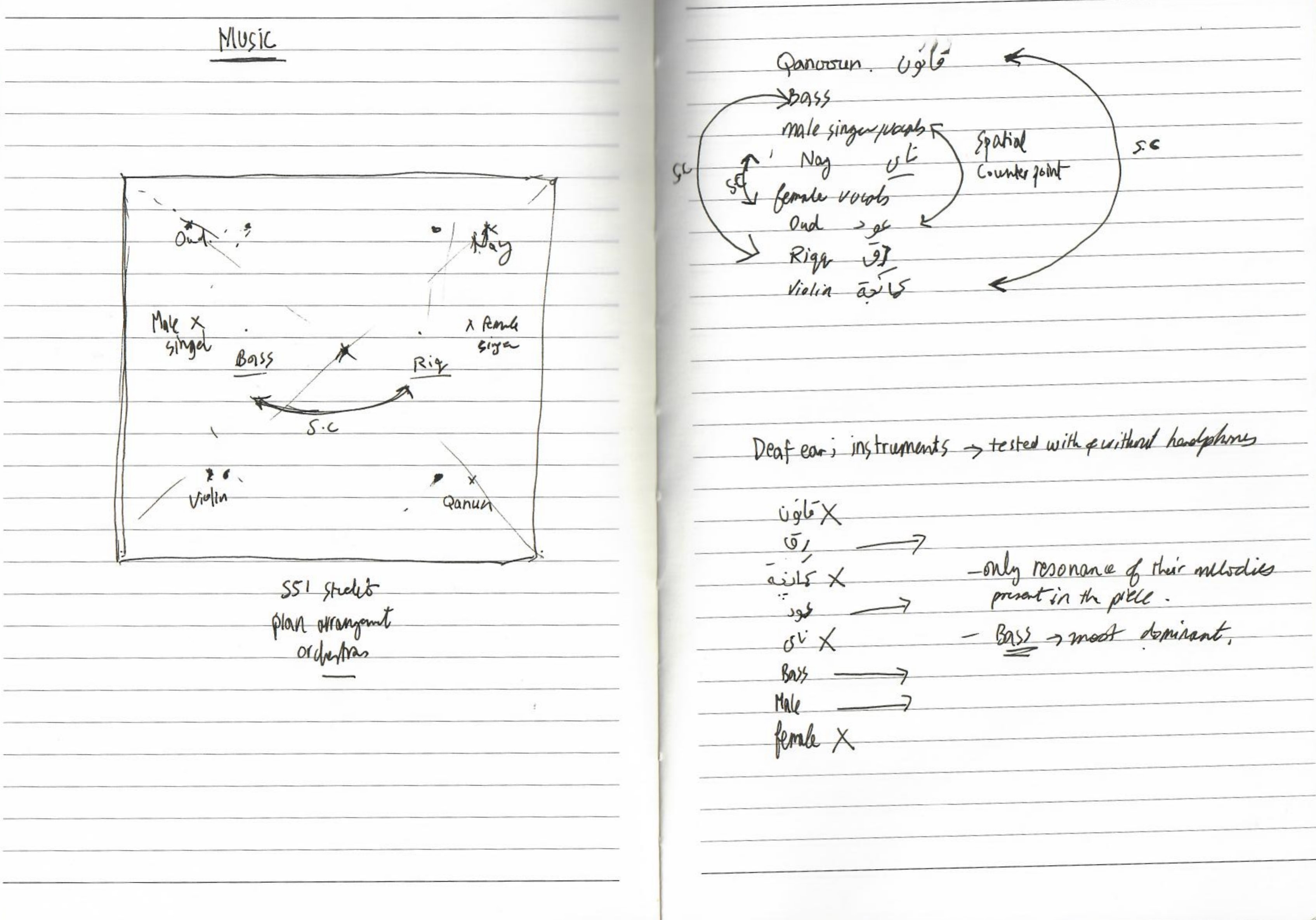

With stem files of a rendition of an Andalusian poem/song, the different instruments were placed across the studio with spatial counterpoints arranged opposite to each other. One of the conclusions of experimenting with music and spatial sounds is that for the deaf ear recording, centering all the instruments to come out of one sound source enhanced the musical experience while arranging them across the studio was recommended for the implanted ear adaptation. This study could possibly be expanded and tailored to different music genres to help improve music perception and sound quality for the d/Deaf community.

Given that one of the main goals of this project is to raise awareness and initiate a dialogue about sound urbanism, I felt it was essential to make the installation interactive so visitors could collaborate towards the sound study. A controller was modelled to permit a smooth transition and shuffle between the three modes of sound, allowing for easier detection of sonic variations.

Converted web version of the piece and the interface that was provided to the audience. Click on play/pause symbol to start the

sound and then click on either the deaf symbol, average ear or cochlear implant to switch between the ways of listening.

Recommended Browser: Google Chrome

The questions and conversations that followed the presentation were particularly important to me, as it demonstrated the idea of the subjectivity of sound. For instance, when the deaf ear recording was being played, one audience member felt alienated by the silence, while another felt at ease. These discussions raised questions and concerns about intersensoriality, which was present in all three sound pieces. More data is still required, as is raising awareness about hearing and sensory capacities for various communities in different sound settings. More data is still required to document and study spatial navigation for people with hearing and sensory disabilities, not only to find solutions but at least as a mode of representation and epistemic activism.

Cities of the d/Deaf is an ongoing project that I am hoping to expand to other cities and spaces, it is also an invitation to d/Deaf artists to participate and share their sonic realities. As said, more data is still required, not only to come up with inclusive solutions in design fields such as architecture and urban design, but also to understand the different cultural communities and their different relationships with the sonic and the spatial.

Related: