Learning to Listen Again (2017)

John Connell

category:

Essay

date:

May 2017

author:

John Connell

published by:

TEDxDanubia

Essay

date:

May 2017

author:

John Connell

published by:

TEDxDanubia

4DSOUND’s creative director John Connell examines the impact of noise pollution in our physical and digital spaces, and new directions made available by focused listening practices and spatial sound technologies.

This essay was originally published in the TXD Idea Book as part of 4DSOUND’s collaboration with TEDxDanubia in May 2017, discussing practices and ideas to facilitate healthier, better connected societies.

What does it mean to listen?

If you were to ask the average person this question, they might respond that we listen to music for enjoyment, we usually listen to what people are saying in conversations, we listen to the world around us as we go about our lives, moving around the city, knowing when the train is about to arrive, and so on.

They might mention that to listen means to hear, and is therefore one of the senses, like sight, taste and touch, or that our ability to enjoy music adds an emotional richness or colour to life. But beyond that, there might not seem much to say- it appears so unremarkable, a process unconsciously running in the background as we go about our days, we’re barely aware that is even happening. It is often only when we are faced with a dramatic change- a venture into the comparative silence of the remote countryside, a self-imposed retreat from daily life, or suffering hearing impairment of some kind- that we suddenly recognise how our ability to listen shapes our existence in a fundamental way.

In fact, the quality of how we listen underpins our very notion of reality, of our consciousness. It influences every aspect of how we think, feel and communicate. Yet sound plays a diminished role in contemporary global culture. In our dense cities and the fragmented, screen-based digital mediascape that we are plugged in to for most of our waking hours, sound plays the poor cousin, a supporting act to the vivid colour and explicit symbolic power of the visual sense. In this essay we’ll consider the impact this has on us as individuals physically and psychologically, on our social interactions, and the spaces we share.

Crucially, we’ll look at what new spatial sound technologies and focused listening practices can offer us in the overwhelming information flood of our mediascapes- and the consequences of ignoring the values that listening represents, as we rush headlong into the age of immersive technologies, likely to shape us more than we shape them.

![]()

Visitors taking time to reflect during a 4DSOUND spatial sound performance at Berlin Atonal

Credit: Camille Blake

Now let us rephrase the question.

What does it mean to truly listen?

Listening is, in essence, the act of attention. It is the intent to bring acuity to our experience as it is unfolding, moment to moment. Listening is something embodied: it is not a passive state, something inevitable, a byproduct of simply being able to hear sounds via our ears. It is something physical, vibration felt on the skin, in the tissues and cavities of the body. So when we truly listen, we access a more direct physicality of experience; literally, a receptivity to signals we are receiving from beyond our physical sensory boundaries, our skin. Think on this for a moment, where you are right now: when you hear a sound or feel even the most subtle of vibrations, be it the wind from the open window tickling the hairs on your arm, or a tremour through the table as your partner slams the front door, you are directly experiencing waves of acoustic pressure caused by energetic changes in the environment. These waves contain information that we have evolved to detect: to perceive (via the senses) and parse (via mental or neural processing) a defined ‘sound’ is to work with biological developments that are many millions of years old, as psychologist and audio neuroscientist Seth Horowitz outlines in The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes The Mind (1).

This in itself is fascinating. We are the benefactors of an evolutionary process which links us to the exploratory threat-and-opportunity tools of some of the earliest life on earth: amoebas detecting proximity and distance of predator, prey or potential partner as they floated through the seas. To fully recognise this is to instantly reframe the partisan, self-oriented temporal frame of our attentions, and invite a wider awareness, beyond our common capacity to imagine our ancestors, so removed by time, scale and complexity. This process of vibration detection is something fundamental to how living organisms interact with their environment.

The process of sensing sound is inherently spatial in nature. The acoustic waves reflecting onto us carry information from which we can determine the dimensions of the space and energy around us. We recognize our environment by the reflections coming from objects like walls or trees; their location and distance, the dimension and angles of their surfaces and the character of their surfaces (hard and smooth or coarse and porous, for example). We detect how objects are behaving, marked by any vibrational signatures they make; the path they take through the space around, above, below or even through us, and an incredibly complex range of attributes that we can interpret as movements in three dimensions: whether they are accelerating or slowing, turning, spinning, arcing; whether they are dense or hollow, or even changing shape as we listen, expanding, shrinking, atomising or coalescing.

To listen, then, is to listen to space. Our ability to perceive the noise, through our senses, and parse this as meaningful signals, through mental processing, defines our spatial cognition, our mental map of the world and how we exist within it- our sense of spatial reality. Every action we take influences this same environment, sending energetic patterns rippling out. We are not separate from the space we are experiencing, but also shaping it, moment-to-moment. This same sensitivity for pattern recognition, our ability to sift through finer and finer nuance of information, enables us to recognise our inner space, both physical and psychological. Physical, in that we can detect vibrations in our tissue and cavities, and define meaning from it: changes in heat, blood flow, muscle contraction and pain reception. Psychological, in identifying patterns- manifestation and repetition of mental images, memories and their associative emotional states- and the causal link between the domains of mind and body.

Consider the implications: by working to refine our natural capacity to understand space through listening, we can gain a deeper awareness of our environment, the effect it has on us individually, and our effect on the environment and others as we think, feel and act within it.

Where might such an ability go if we fully refine our listening capacities? What impact can this have on how we build our environments, the interactions we create between us, and our understanding of ourselves as ‘experiencing organisms’? If over millions of years we have learned to detect a range of complex spatial energetic patterns through listening, what new movements and signatures can we learn to recognise as we become even more adept- information that is already in our environment but is as yet beyond our ability to define it? As we shift into a new era of immersive technology and media, what might the role of sound and listening be in shaping these mediated experiences in a positive way? Most crucially, when we recognise the critical social and environmental problems we face globally, how can such tools and practices help us find solutions?

![]()

People listening during a sound installation at the Spatial Sound Institute, Budapest. Credit: Georg Schroll

These are the type of questions we are asking at 4DSOUND. Established in 2007, 4DSOUND is a platform for developing spatial sound technologies and cultivating listening as a discipline. Centred around the Spatial Sound Institute, our research facility in Budapest, Hungary, we work with artists, technologists, scientists and theorists to qualitatively improve our environments, our interactions and personal experiences. Our mission stems from a belief that we are missing out on certain ways of interacting with sound today, due to the way our culture, and technologies, are evolving.

Our work draws, at least in spirit, on investigations into sound and listening that date back centuries, possibly even millennia. From the rich history of 20th century music and especially from the field of acoustic ecology, as investigated by R. Murray Schafer in The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (2),we have learnt how to listen to subtleties of our worldly soundscape- to appreciate them for their musicality and the diversity of information about our environment that they can provide us. The ‘cracks in the wall’ of the Western concert hall as a concept, instigated by the work and thought of John Cage and particularly manifested in the piece 4’33” (1952), highlighted the act of listening as an activity that can change, influence and create what one is listening to, as opposed to passively perceiving it. Yoko Ono’s conceptual works from the book Grapefruit (3) exemplify the process of listening as an essentially creative one. Listening to “the sound of stone aging” or “room breathing” are evoking acts of inner imagination, where listening becomes equivalent to consciously thinking about sound.

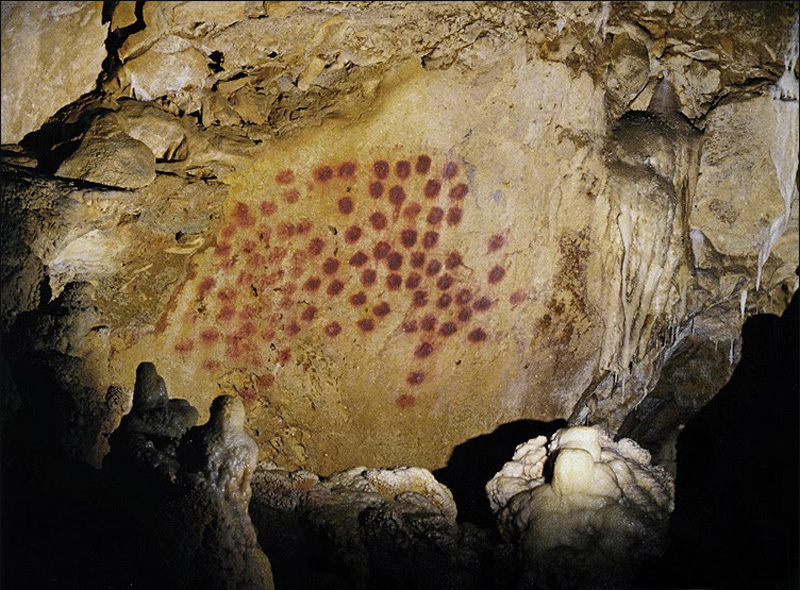

Interpretation of listening as a conscious activity is the basis of ‘sound walks’ as an artistic practice, as famously employed by Max Neuhaus in the 1970s. These walks rely on the idea that the city soundscape is already a composition on its own and that the ear that hears and deciphers it, is the performer. Such attention to sound, our ability to listen and make sense of the environment, has origins going back to the deep pre-history of humanity. Ancient men and women started to explore caves 35 thousand years ago, entering unknown space either in the pitch dark, or illuminated only by torch-flame. According to recent research by Prof S. Errede as published in Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves (4), the presence of wall paintings and drawings in the majority of caves correlates with the phenomenon of natural echo found at the site, and especially so at particular resonant frequencies.

The specific locations of these sites were not co-incidental. As Prof. Errede outlines, our ancestors were not indulging in random cave graffiti: precise codification of the cave’s resonant sound has been established in the paintings, indicated by lines or dots emerging from the mouths or the figures and animals drawn. Such markings at particular locations in the caves suggest an exceptional ability to understand the characteristics of the space through listening. It gives us an insight into the refined ways our ancestors must have relied on listening to navigate, and understand, their world.

![]()

A photograph from Grotto du Pech Merle in the Occitania region, France. The red dots indicate a zone of acoustic significance, with distinct resonance. Image: unknown

Advanced practices working with sound and listening played central roles in many early spiritual disciplines. Around the sixth century BCE, yogic philosophy began to emerge in India. Different schools of Hinduism and later the sister tradition of Buddhism then spread across the region with the intent, amongst other goals, of practitioners attaining moksha or nirvana, meaning liberation, from the illusory nature of the Self- the psychological construct of identity- and a direct experience of the true nature of reality.

Alongside mantra, words and phrases believed by the practitioner to convey spiritual and psychological power, many schools developed intensive meditation techniques. States of heightened consciousness were attained by shifting between global and local awareness: global, as in listening and sensing information from the surrounding environment to objectively recognise its influence on consciousness; local, as in single-point mental focus, allowing the meditator to move deeply into the subjectively experienced phenomena of mind and body.

The Vipassana technique of bodyscanning demonstrates the capabilities of such focused attention. Bodyscanning aims to heighten sensitivity, and access refined patterns of psycho-physical information. In a sufficiently attuned state, the perception of a pain in the leg can shift from a vaguely localised sensation of ‘pain’, into a more complex awareness of the character of the signals (pulsing, throbbing, twitching et cetera).

With further introspection, experienced practitioners claim to have a direct experience of the electrical signals and neuro-chemical response patterns; as the meditator continues to objectively examine the ‘pain’, and the psycho-emotional pattern of aversion associated with it, she can recognise it is not the fixed mental form it appears to be: that such ‘gross’ surface level patterns are illusory, and a direct experience with the ‘subtle’ phenomena as it happens is possible.

This shows us that the experience of thoughts and physical sensations in the body is dependent on the perceiver’s ability to effectively receive and parse the information. With enough practice, the meditator can move past the mental ‘labelling’ of stimulus- whether it be pain, pleasure or otherwise- and the subsequent impulse to respond, finding a new mastery over their conscious experience.

This really underlines the power of listening as a discipline: by refining our ability to understand the sensory information we receive, we gain insight into the mechanics of our experience, including how our own faculties subjectively shape the parameters of our consciousness. This allows us to act with more clarity and intelligence, less reaction and impartiality.

Given the serious challenges we face globally, the importance of this shouldn’t be underestimated. Cultivating our ability to listen, both literally and metaphorically, helps us communicate more meaningfully, bridge differences through the cultivation of compassion, and find more intelligent ways through the sense of growing social, environmental and political dysfunction and imbalance.

Meditation has seen something of a boom in The West, with apps like Headspace gaining popularity, so there is clearly recognition of its value in our hectic lives (5). Sadly, there are still few opportunities to explore such practices in mainstream culture. This is largely because the very idea of listening and the reflection it encourages are not part of how our environments function: they are quite simply not supportive of listening. Noise pollution in our cities means on average we live and work with a constant noise of 60db or higher surrounding us. The range of silent sounds being cut out from the environmental soundscape by masking noise is a direct manifestation of what Murray Schafer has described as “universal deafening” (2). Murray Schafer suggested in the 1970’s that noise pollution would become a worldwide problem, unless it could be brought quickly under control. Since then, the situation has worsened worldwide in both public and private spaces.

![]()

The city and its growing noise: Murray Schafer’s ‘universal deafening.’ Image: Bobby Anwar

Such levels of ambient noise are, at least subconsciously, associated with a sense of disquiet and unease, potentially triggering the sympathetic nervous system, which controls our fight-or-flight response. And as it narrows the dynamic range of our hearing, it is arguably damaging our long-term ability to pick out finer, softer sounds, and therefore the aptitude, and appetite, for this sensitivity in our interactions and exchanges.

Our response is to fight fire with fire. We shout to make ourselves heard above the din in poor acoustically designed spaces, background muzak filling in any chance of silence. We avoid listening, drowning out the surrounding cacophony entirely, shutting ourselves off through white earbuds streaming low quality mp3s: creating ‘millions of tiny little sound bubbles’, as Julian Treasure outlines in his 2011 TED talk, ‘in which nobody is listening to anybody.’ (6) Moreover, this kind of music consumption arguably exacerbates feelings of disquiet: a recent study from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology shows low quality mp3 compression heightens negative emotional associations of music (feelings such as ‘sad’,’shy’ and ‘scary’) and weakens positive ones (‘happy’, ‘romantic’, ‘calm’) (7). The sound we use to block out our environmental noise pollution might actually contribute to additional levels of stress. The hegemony of visual media plays a crucial role in our dis-ability to listen. The majority of our waking hours are spent staring at screens, peering through windows into a world in which sound plays little more than a supporting role (think: the cartoonish sound design of messaging apps; the interchangeable background muzak of quick-fix news reports). This vast mediascape of information, and mental stimulation, was unimaginable even 20 years ago. From an evolutionary standpoint, we’ve opened Pandora’s Box: we are not equipped for the psycho-physiological effects of this infinite stream of stimulation, and we’ve yet to create effective filters.

![]()

Filtering the noise of our digital spaces

We now live in an attention economy, with a barrage of voices competing for as many seconds and minutes of your time as possible. This has engendered the design of an information-as-entertainment culture that defers to immediacy over depth, sound-bites over full narratives, convenience over quality, novelty over the familiar, shock over nuance and titillation over reflection. It’s not that we don’t want it, but whether it’s what we need is a different matter. We struggle against this unending tide, and our best attempts at filtering create further problems: we’re increasingly residents of algorithm-enhanced echo chambers, where we only see and hear what we want to, isolating us from important social dialogues and global crises we’re happy to avoid. With new solutions come new problems: where for centuries we struggled from information poverty, we now actively practice information avoidance, ‘selecting our own reality by deliberately avoiding information that threatens <our> happiness and wellbeing’, as a paper published from Carnegie Mellon academics outlines (8).

Most of the digital real estate we spend our time on has been constructed on the attention economy principle, and much of it is owned by the same people: the real-time stream of Facebook and Twitter, visual immediacy of Instagram, Youtube and Snapchat, the long-read of Kindle and Medium. In these domains, attention is money: one way or another, your consciousness is for sale. And as we’ve seen with the emerging tactics of ‘fake news’, actively spreading dis-information joins pseudo-science, superficial ‘hot-take’ journalism and ‘native’ advertising routinely presented as legitimate media, creating an information environment that is agenda-ised, deliberately misleading, conflicting, inaccurate and untrustworthy.

Nevertheless, as the engine of so much progress, innovation and social change, of course we have to recognise the huge potential of the tools at our disposal. But we are rarely cognisant of the effect of our media technologies, and how quickly they are evolving. How we process information is beginning to change, particularly in younger generations. 2015 research by Microsoft Canada claimed that heavy media users, especially those in their late teens and early twenties, were able to now ‘frontload’ information in bursts of ‘high attention’, with better retention of details in short spaces of time. Conversely, attention spans have dropped from 12 to 8 seconds, leading to problems staying focused in environments where longer term attention is needed (including, no doubt, reading this essay) (9).

Our media behaviour is negatively impacting our ability to stay focused, and it has clear negative impact on our motivations and resilience. ‘We now expect immediate gratification for performing tasks’, argues Youtuber exurbia in his March 2017 upload ‘How we might’ve Fucked our Attention Spans’, ‘so when a book gets a bit boring… or learning an instrument gets tough… or we get stuck alone with our own thoughts, we switch to doing something mediocre online, rather than persevering with something difficult in the real world’ (10).

This drive for gratification in our online behaviour bears all the hallmarks of addiction, something author Steven Kotler outlines as part of what he terms the ‘Altered State Economy’. We consume media to alter our waking states of consciousness, essentially to get high, via dopamine rush which beyond making us feel pleasure, is ‘a focusing, performance-enhancing drug’.

Formation of habitual usage of social media, emotionally evocative news and entertainment, and porn, stems from how they activate the brain’s reward centres. ‘What we’re seeing is people using a device to get at their underlying neurochemistry, and it’s very addictive <behaviour>’ states Kotler (11).

There is a stupefying quality to how we consume media which indicates a sense of unrest, a need for distraction, or coping mechanism to avoid discomfort or even psychological trauma. And just as with other addictive behaviour, an overemphasis on habitual consumption does not ultimately satisfy or make us happy. In his New Internationalist article ‘The Demoralised Mind’, retired psychology academic John F Schumacher writes:

‘Consumption itself is a flawed motivational platform for a society. Repeated consummation of desire, without moderating constraints, only serves to habituate people and diminish the future satisfaction potential of what is consumed. This develops gradually into ‘consumer anhedonia’, wherein consumption loses reward capacity and offers no more than distraction and ritualistic value. Consumerism and psychic deadness are inexorable bedfellows.’ (12)

This is not to dismiss the pretty radical democratisation of digital tools that has emerged from consumer culture. But the output of this ‘content’- be it graphic design, photography, music, dance or otherwise- is commoditised as units for consumption, valued primarily by popularity and commercial success. And over-emphasis on consumption, no matter how creative, does not deliver the meaning we seem to collectively crave. As we increasingly disengage with institutionalised belief systems in a climate of socio-economic uncertainty- religion, the state, even community in some cases the result, as Schumacher is suggesting, is endemic demoralisation. We have stumbled into the Age of Passivity, empowered with astonishing choice, yet increasingly unfulfilled, using consumption and novelty to distance us from a sense of existential disquiet. For many, the world we are connected to, and the issues we are presented, with seem too distant, too gigantic, beyond our ability to change. Or, perhaps soberingly- simply too much effort.

Arguably, the solution does not lie in the current social, technological hierarchies and cultural ideologies. Schumacher cites the social psychologist Erich Fromm: ‘We can’t make people sane by making them adjust to this society. We need a society that is adjusted to the needs of people.’ If we recognise we are undergoing what Schumacher terms a kind of ‘psychospiritual crisis’ in our post-truth, postreligion world, we must identify and define new purpose, new meaning, and tools and practices which enable and empower us collectively.

Do our media spaces and our technology serve us to these ends- when we recognise the gulf between consumer choice and fulfilment, between information and pro-active response? As we enter a new phase in immersive technology, intelligent environments and machine intelligence, is it likely that we can tackle these issues more effectively, or will they reinforce the problems? How actively are we involved in designing the new spatial realities of an immersive technological future?

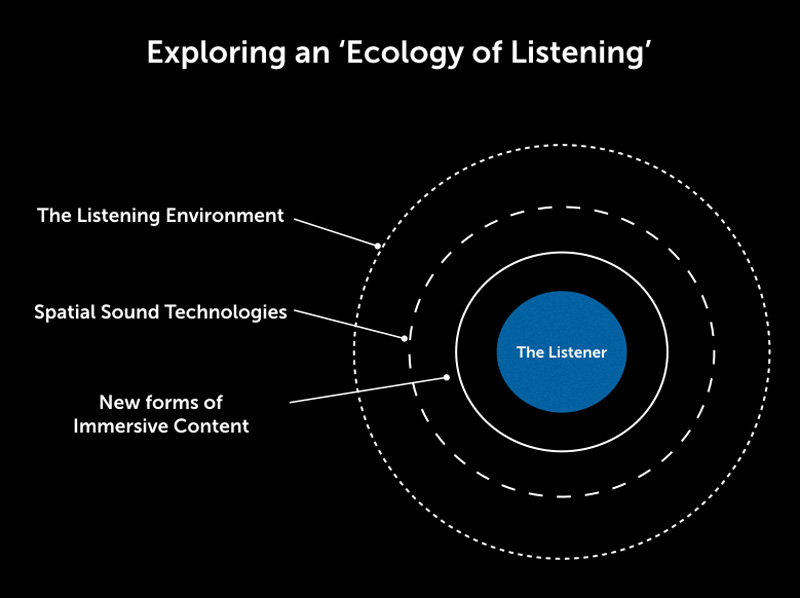

There are no easy answers to these questions, but elevating the value of listening in culture can help us explore new ways of thinking and feeling about our physical, psychological and digital spaces. Our work at 4DSOUND investigates what we call an Ecology of Listening: a systemic improvement in our listening environment to enhance our mental and physical state of being.

![]()

Exploring an Ecology of Listening

Here are some considerations that have come out of this approach, and offer up new possibilities to explore. If listening culture teaches us anything, it is that by taking time to stop and reflect together, there are always better answers waiting to be discovered- if we allow them to emerge.

Listening makes the invisible tangible.

There is information all around us in the form of vibration, much of it outside our capacity to detect. An embodied listening practice can bring us closer to the thresholds of the known — the very borders of our consciousness. By sharpening this ‘perception at the edge of the new’, as Deep Listening pioneer Pauline Oliveros termed it (13), we can gain direct experience of this liminality, and reach out into new states of sensing and awareness.

Listening can help us imagine new futures.

From this state of receptivity, we are able to think, act and respond creatively to our experience as it unfolds. We can gain inspiration on the kind of spaces we want to build- and how we want to live within them.

Listening requires a new form of language.

As our abilities to work with sound and space begin to improve, we need to build a semantics of spatial sound that clearly defines the underlying patterns we are beginning to identify, and our physiological reception of them. As examples, effective frequencies, rhythms and sonic textures expressed in a spatial sound environment can encourage specific outcomes: memory recall, associative visualisation and creative problem solving.

![]() Listening and spatial sound technologies enable us to evolve both our expectations of, and practice with, sound and music culture.

Listening and spatial sound technologies enable us to evolve both our expectations of, and practice with, sound and music culture.

Listening opens up new musical aesthetics.

As we develop new conceptions of space, artists will begin working with new forms of aesthetics in response. We are seeing a shift towards more spatially expansive, materially minimal, durational soundscapes that open up highly refined psychological and emotional states and stimulate a more creative, participative role for the listeners.

Listening needs time and space to emerge.

Accessing the intelligence in listening needs to be cultivated. It requires ongoing practice in the right kind of environment. The more we can build moments of quiet reflection in our busy days, and the more access we have to spaces that encourage reflection and silence, the more our ability to work with listening will deepen and expand.

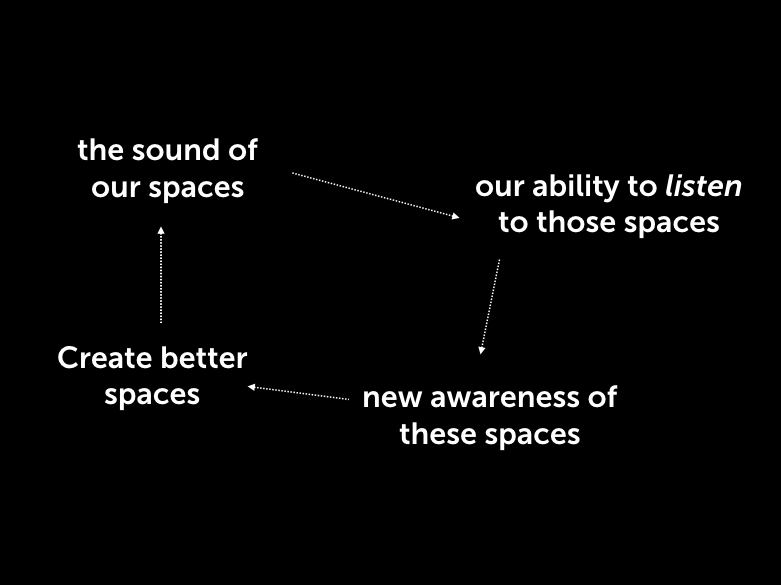

![]() The virtuous cycle of tuning into the sound of our spaces.

The virtuous cycle of tuning into the sound of our spaces.

Listening helps us create healthier social spaces.

Ultimately, listening can help us create more balance in how we design our shared spaces and how we envision our interactions within them. When our environment is designed to minimise noise pollution and encourage more intelligible communication, we are much more likely to enjoy, and be nourished by, our spaces.

—

Text by John Connell

If you were to ask the average person this question, they might respond that we listen to music for enjoyment, we usually listen to what people are saying in conversations, we listen to the world around us as we go about our lives, moving around the city, knowing when the train is about to arrive, and so on.

They might mention that to listen means to hear, and is therefore one of the senses, like sight, taste and touch, or that our ability to enjoy music adds an emotional richness or colour to life. But beyond that, there might not seem much to say- it appears so unremarkable, a process unconsciously running in the background as we go about our days, we’re barely aware that is even happening. It is often only when we are faced with a dramatic change- a venture into the comparative silence of the remote countryside, a self-imposed retreat from daily life, or suffering hearing impairment of some kind- that we suddenly recognise how our ability to listen shapes our existence in a fundamental way.

In fact, the quality of how we listen underpins our very notion of reality, of our consciousness. It influences every aspect of how we think, feel and communicate. Yet sound plays a diminished role in contemporary global culture. In our dense cities and the fragmented, screen-based digital mediascape that we are plugged in to for most of our waking hours, sound plays the poor cousin, a supporting act to the vivid colour and explicit symbolic power of the visual sense. In this essay we’ll consider the impact this has on us as individuals physically and psychologically, on our social interactions, and the spaces we share.

Crucially, we’ll look at what new spatial sound technologies and focused listening practices can offer us in the overwhelming information flood of our mediascapes- and the consequences of ignoring the values that listening represents, as we rush headlong into the age of immersive technologies, likely to shape us more than we shape them.

Visitors taking time to reflect during a 4DSOUND spatial sound performance at Berlin Atonal

Credit: Camille Blake

Now let us rephrase the question.

What does it mean to truly listen?

Listening is, in essence, the act of attention. It is the intent to bring acuity to our experience as it is unfolding, moment to moment. Listening is something embodied: it is not a passive state, something inevitable, a byproduct of simply being able to hear sounds via our ears. It is something physical, vibration felt on the skin, in the tissues and cavities of the body. So when we truly listen, we access a more direct physicality of experience; literally, a receptivity to signals we are receiving from beyond our physical sensory boundaries, our skin. Think on this for a moment, where you are right now: when you hear a sound or feel even the most subtle of vibrations, be it the wind from the open window tickling the hairs on your arm, or a tremour through the table as your partner slams the front door, you are directly experiencing waves of acoustic pressure caused by energetic changes in the environment. These waves contain information that we have evolved to detect: to perceive (via the senses) and parse (via mental or neural processing) a defined ‘sound’ is to work with biological developments that are many millions of years old, as psychologist and audio neuroscientist Seth Horowitz outlines in The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes The Mind (1).

This in itself is fascinating. We are the benefactors of an evolutionary process which links us to the exploratory threat-and-opportunity tools of some of the earliest life on earth: amoebas detecting proximity and distance of predator, prey or potential partner as they floated through the seas. To fully recognise this is to instantly reframe the partisan, self-oriented temporal frame of our attentions, and invite a wider awareness, beyond our common capacity to imagine our ancestors, so removed by time, scale and complexity. This process of vibration detection is something fundamental to how living organisms interact with their environment.

The process of sensing sound is inherently spatial in nature. The acoustic waves reflecting onto us carry information from which we can determine the dimensions of the space and energy around us. We recognize our environment by the reflections coming from objects like walls or trees; their location and distance, the dimension and angles of their surfaces and the character of their surfaces (hard and smooth or coarse and porous, for example). We detect how objects are behaving, marked by any vibrational signatures they make; the path they take through the space around, above, below or even through us, and an incredibly complex range of attributes that we can interpret as movements in three dimensions: whether they are accelerating or slowing, turning, spinning, arcing; whether they are dense or hollow, or even changing shape as we listen, expanding, shrinking, atomising or coalescing.

Listening is, in essence, the act of attention. It is the intent to bring acuity to our experience as it is unfolding, moment to moment.

To listen, then, is to listen to space. Our ability to perceive the noise, through our senses, and parse this as meaningful signals, through mental processing, defines our spatial cognition, our mental map of the world and how we exist within it- our sense of spatial reality. Every action we take influences this same environment, sending energetic patterns rippling out. We are not separate from the space we are experiencing, but also shaping it, moment-to-moment. This same sensitivity for pattern recognition, our ability to sift through finer and finer nuance of information, enables us to recognise our inner space, both physical and psychological. Physical, in that we can detect vibrations in our tissue and cavities, and define meaning from it: changes in heat, blood flow, muscle contraction and pain reception. Psychological, in identifying patterns- manifestation and repetition of mental images, memories and their associative emotional states- and the causal link between the domains of mind and body.

Consider the implications: by working to refine our natural capacity to understand space through listening, we can gain a deeper awareness of our environment, the effect it has on us individually, and our effect on the environment and others as we think, feel and act within it.

Where might such an ability go if we fully refine our listening capacities? What impact can this have on how we build our environments, the interactions we create between us, and our understanding of ourselves as ‘experiencing organisms’? If over millions of years we have learned to detect a range of complex spatial energetic patterns through listening, what new movements and signatures can we learn to recognise as we become even more adept- information that is already in our environment but is as yet beyond our ability to define it? As we shift into a new era of immersive technology and media, what might the role of sound and listening be in shaping these mediated experiences in a positive way? Most crucially, when we recognise the critical social and environmental problems we face globally, how can such tools and practices help us find solutions?

People listening during a sound installation at the Spatial Sound Institute, Budapest. Credit: Georg Schroll

These are the type of questions we are asking at 4DSOUND. Established in 2007, 4DSOUND is a platform for developing spatial sound technologies and cultivating listening as a discipline. Centred around the Spatial Sound Institute, our research facility in Budapest, Hungary, we work with artists, technologists, scientists and theorists to qualitatively improve our environments, our interactions and personal experiences. Our mission stems from a belief that we are missing out on certain ways of interacting with sound today, due to the way our culture, and technologies, are evolving.

Our work draws, at least in spirit, on investigations into sound and listening that date back centuries, possibly even millennia. From the rich history of 20th century music and especially from the field of acoustic ecology, as investigated by R. Murray Schafer in The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (2),we have learnt how to listen to subtleties of our worldly soundscape- to appreciate them for their musicality and the diversity of information about our environment that they can provide us. The ‘cracks in the wall’ of the Western concert hall as a concept, instigated by the work and thought of John Cage and particularly manifested in the piece 4’33” (1952), highlighted the act of listening as an activity that can change, influence and create what one is listening to, as opposed to passively perceiving it. Yoko Ono’s conceptual works from the book Grapefruit (3) exemplify the process of listening as an essentially creative one. Listening to “the sound of stone aging” or “room breathing” are evoking acts of inner imagination, where listening becomes equivalent to consciously thinking about sound.

Where might our abilities go if we fully refine our listening capacities? What impact could this have on how we build our environments, the interactions we create between us, and our understanding of ourselves as ‘experiencing organisms’

Interpretation of listening as a conscious activity is the basis of ‘sound walks’ as an artistic practice, as famously employed by Max Neuhaus in the 1970s. These walks rely on the idea that the city soundscape is already a composition on its own and that the ear that hears and deciphers it, is the performer. Such attention to sound, our ability to listen and make sense of the environment, has origins going back to the deep pre-history of humanity. Ancient men and women started to explore caves 35 thousand years ago, entering unknown space either in the pitch dark, or illuminated only by torch-flame. According to recent research by Prof S. Errede as published in Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves (4), the presence of wall paintings and drawings in the majority of caves correlates with the phenomenon of natural echo found at the site, and especially so at particular resonant frequencies.

The specific locations of these sites were not co-incidental. As Prof. Errede outlines, our ancestors were not indulging in random cave graffiti: precise codification of the cave’s resonant sound has been established in the paintings, indicated by lines or dots emerging from the mouths or the figures and animals drawn. Such markings at particular locations in the caves suggest an exceptional ability to understand the characteristics of the space through listening. It gives us an insight into the refined ways our ancestors must have relied on listening to navigate, and understand, their world.

A photograph from Grotto du Pech Merle in the Occitania region, France. The red dots indicate a zone of acoustic significance, with distinct resonance. Image: unknown

Advanced practices working with sound and listening played central roles in many early spiritual disciplines. Around the sixth century BCE, yogic philosophy began to emerge in India. Different schools of Hinduism and later the sister tradition of Buddhism then spread across the region with the intent, amongst other goals, of practitioners attaining moksha or nirvana, meaning liberation, from the illusory nature of the Self- the psychological construct of identity- and a direct experience of the true nature of reality.

Alongside mantra, words and phrases believed by the practitioner to convey spiritual and psychological power, many schools developed intensive meditation techniques. States of heightened consciousness were attained by shifting between global and local awareness: global, as in listening and sensing information from the surrounding environment to objectively recognise its influence on consciousness; local, as in single-point mental focus, allowing the meditator to move deeply into the subjectively experienced phenomena of mind and body.

The Vipassana technique of bodyscanning demonstrates the capabilities of such focused attention. Bodyscanning aims to heighten sensitivity, and access refined patterns of psycho-physical information. In a sufficiently attuned state, the perception of a pain in the leg can shift from a vaguely localised sensation of ‘pain’, into a more complex awareness of the character of the signals (pulsing, throbbing, twitching et cetera).

With further introspection, experienced practitioners claim to have a direct experience of the electrical signals and neuro-chemical response patterns; as the meditator continues to objectively examine the ‘pain’, and the psycho-emotional pattern of aversion associated with it, she can recognise it is not the fixed mental form it appears to be: that such ‘gross’ surface level patterns are illusory, and a direct experience with the ‘subtle’ phenomena as it happens is possible.

This shows us that the experience of thoughts and physical sensations in the body is dependent on the perceiver’s ability to effectively receive and parse the information. With enough practice, the meditator can move past the mental ‘labelling’ of stimulus- whether it be pain, pleasure or otherwise- and the subsequent impulse to respond, finding a new mastery over their conscious experience.

This really underlines the power of listening as a discipline: by refining our ability to understand the sensory information we receive, we gain insight into the mechanics of our experience, including how our own faculties subjectively shape the parameters of our consciousness. This allows us to act with more clarity and intelligence, less reaction and impartiality.

Given the serious challenges we face globally, the importance of this shouldn’t be underestimated. Cultivating our ability to listen, both literally and metaphorically, helps us communicate more meaningfully, bridge differences through the cultivation of compassion, and find more intelligent ways through the sense of growing social, environmental and political dysfunction and imbalance.

Meditation has seen something of a boom in The West, with apps like Headspace gaining popularity, so there is clearly recognition of its value in our hectic lives (5). Sadly, there are still few opportunities to explore such practices in mainstream culture. This is largely because the very idea of listening and the reflection it encourages are not part of how our environments function: they are quite simply not supportive of listening. Noise pollution in our cities means on average we live and work with a constant noise of 60db or higher surrounding us. The range of silent sounds being cut out from the environmental soundscape by masking noise is a direct manifestation of what Murray Schafer has described as “universal deafening” (2). Murray Schafer suggested in the 1970’s that noise pollution would become a worldwide problem, unless it could be brought quickly under control. Since then, the situation has worsened worldwide in both public and private spaces.

The city and its growing noise: Murray Schafer’s ‘universal deafening.’ Image: Bobby Anwar

Such levels of ambient noise are, at least subconsciously, associated with a sense of disquiet and unease, potentially triggering the sympathetic nervous system, which controls our fight-or-flight response. And as it narrows the dynamic range of our hearing, it is arguably damaging our long-term ability to pick out finer, softer sounds, and therefore the aptitude, and appetite, for this sensitivity in our interactions and exchanges.

Our response is to fight fire with fire. We shout to make ourselves heard above the din in poor acoustically designed spaces, background muzak filling in any chance of silence. We avoid listening, drowning out the surrounding cacophony entirely, shutting ourselves off through white earbuds streaming low quality mp3s: creating ‘millions of tiny little sound bubbles’, as Julian Treasure outlines in his 2011 TED talk, ‘in which nobody is listening to anybody.’ (6) Moreover, this kind of music consumption arguably exacerbates feelings of disquiet: a recent study from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology shows low quality mp3 compression heightens negative emotional associations of music (feelings such as ‘sad’,’shy’ and ‘scary’) and weakens positive ones (‘happy’, ‘romantic’, ‘calm’) (7). The sound we use to block out our environmental noise pollution might actually contribute to additional levels of stress. The hegemony of visual media plays a crucial role in our dis-ability to listen. The majority of our waking hours are spent staring at screens, peering through windows into a world in which sound plays little more than a supporting role (think: the cartoonish sound design of messaging apps; the interchangeable background muzak of quick-fix news reports). This vast mediascape of information, and mental stimulation, was unimaginable even 20 years ago. From an evolutionary standpoint, we’ve opened Pandora’s Box: we are not equipped for the psycho-physiological effects of this infinite stream of stimulation, and we’ve yet to create effective filters.

Filtering the noise of our digital spaces

We now live in an attention economy, with a barrage of voices competing for as many seconds and minutes of your time as possible. This has engendered the design of an information-as-entertainment culture that defers to immediacy over depth, sound-bites over full narratives, convenience over quality, novelty over the familiar, shock over nuance and titillation over reflection. It’s not that we don’t want it, but whether it’s what we need is a different matter. We struggle against this unending tide, and our best attempts at filtering create further problems: we’re increasingly residents of algorithm-enhanced echo chambers, where we only see and hear what we want to, isolating us from important social dialogues and global crises we’re happy to avoid. With new solutions come new problems: where for centuries we struggled from information poverty, we now actively practice information avoidance, ‘selecting our own reality by deliberately avoiding information that threatens <our> happiness and wellbeing’, as a paper published from Carnegie Mellon academics outlines (8).

Most of the digital real estate we spend our time on has been constructed on the attention economy principle, and much of it is owned by the same people: the real-time stream of Facebook and Twitter, visual immediacy of Instagram, Youtube and Snapchat, the long-read of Kindle and Medium. In these domains, attention is money: one way or another, your consciousness is for sale. And as we’ve seen with the emerging tactics of ‘fake news’, actively spreading dis-information joins pseudo-science, superficial ‘hot-take’ journalism and ‘native’ advertising routinely presented as legitimate media, creating an information environment that is agenda-ised, deliberately misleading, conflicting, inaccurate and untrustworthy.

When we recognise the gulf between consumer choice and fulfilment, can we say our media spaces serve us well enough? As we enter a new era of immersive technology, is it likely that we can tackle these issues more effectively, or will they reinforce the problems?

Nevertheless, as the engine of so much progress, innovation and social change, of course we have to recognise the huge potential of the tools at our disposal. But we are rarely cognisant of the effect of our media technologies, and how quickly they are evolving. How we process information is beginning to change, particularly in younger generations. 2015 research by Microsoft Canada claimed that heavy media users, especially those in their late teens and early twenties, were able to now ‘frontload’ information in bursts of ‘high attention’, with better retention of details in short spaces of time. Conversely, attention spans have dropped from 12 to 8 seconds, leading to problems staying focused in environments where longer term attention is needed (including, no doubt, reading this essay) (9).

Our media behaviour is negatively impacting our ability to stay focused, and it has clear negative impact on our motivations and resilience. ‘We now expect immediate gratification for performing tasks’, argues Youtuber exurbia in his March 2017 upload ‘How we might’ve Fucked our Attention Spans’, ‘so when a book gets a bit boring… or learning an instrument gets tough… or we get stuck alone with our own thoughts, we switch to doing something mediocre online, rather than persevering with something difficult in the real world’ (10).

This drive for gratification in our online behaviour bears all the hallmarks of addiction, something author Steven Kotler outlines as part of what he terms the ‘Altered State Economy’. We consume media to alter our waking states of consciousness, essentially to get high, via dopamine rush which beyond making us feel pleasure, is ‘a focusing, performance-enhancing drug’.

Formation of habitual usage of social media, emotionally evocative news and entertainment, and porn, stems from how they activate the brain’s reward centres. ‘What we’re seeing is people using a device to get at their underlying neurochemistry, and it’s very addictive <behaviour>’ states Kotler (11).

There is a stupefying quality to how we consume media which indicates a sense of unrest, a need for distraction, or coping mechanism to avoid discomfort or even psychological trauma. And just as with other addictive behaviour, an overemphasis on habitual consumption does not ultimately satisfy or make us happy. In his New Internationalist article ‘The Demoralised Mind’, retired psychology academic John F Schumacher writes:

‘Consumption itself is a flawed motivational platform for a society. Repeated consummation of desire, without moderating constraints, only serves to habituate people and diminish the future satisfaction potential of what is consumed. This develops gradually into ‘consumer anhedonia’, wherein consumption loses reward capacity and offers no more than distraction and ritualistic value. Consumerism and psychic deadness are inexorable bedfellows.’ (12)

This is not to dismiss the pretty radical democratisation of digital tools that has emerged from consumer culture. But the output of this ‘content’- be it graphic design, photography, music, dance or otherwise- is commoditised as units for consumption, valued primarily by popularity and commercial success. And over-emphasis on consumption, no matter how creative, does not deliver the meaning we seem to collectively crave. As we increasingly disengage with institutionalised belief systems in a climate of socio-economic uncertainty- religion, the state, even community in some cases the result, as Schumacher is suggesting, is endemic demoralisation. We have stumbled into the Age of Passivity, empowered with astonishing choice, yet increasingly unfulfilled, using consumption and novelty to distance us from a sense of existential disquiet. For many, the world we are connected to, and the issues we are presented, with seem too distant, too gigantic, beyond our ability to change. Or, perhaps soberingly- simply too much effort.

Arguably, the solution does not lie in the current social, technological hierarchies and cultural ideologies. Schumacher cites the social psychologist Erich Fromm: ‘We can’t make people sane by making them adjust to this society. We need a society that is adjusted to the needs of people.’ If we recognise we are undergoing what Schumacher terms a kind of ‘psychospiritual crisis’ in our post-truth, postreligion world, we must identify and define new purpose, new meaning, and tools and practices which enable and empower us collectively.

Do our media spaces and our technology serve us to these ends- when we recognise the gulf between consumer choice and fulfilment, between information and pro-active response? As we enter a new phase in immersive technology, intelligent environments and machine intelligence, is it likely that we can tackle these issues more effectively, or will they reinforce the problems? How actively are we involved in designing the new spatial realities of an immersive technological future?

There are no easy answers to these questions, but elevating the value of listening in culture can help us explore new ways of thinking and feeling about our physical, psychological and digital spaces. Our work at 4DSOUND investigates what we call an Ecology of Listening: a systemic improvement in our listening environment to enhance our mental and physical state of being.

Exploring an Ecology of Listening

Here are some considerations that have come out of this approach, and offer up new possibilities to explore. If listening culture teaches us anything, it is that by taking time to stop and reflect together, there are always better answers waiting to be discovered- if we allow them to emerge.

Listening makes the invisible tangible.

There is information all around us in the form of vibration, much of it outside our capacity to detect. An embodied listening practice can bring us closer to the thresholds of the known — the very borders of our consciousness. By sharpening this ‘perception at the edge of the new’, as Deep Listening pioneer Pauline Oliveros termed it (13), we can gain direct experience of this liminality, and reach out into new states of sensing and awareness.

Listening can help us imagine new futures.

From this state of receptivity, we are able to think, act and respond creatively to our experience as it unfolds. We can gain inspiration on the kind of spaces we want to build- and how we want to live within them.

Listening requires a new form of language.

As our abilities to work with sound and space begin to improve, we need to build a semantics of spatial sound that clearly defines the underlying patterns we are beginning to identify, and our physiological reception of them. As examples, effective frequencies, rhythms and sonic textures expressed in a spatial sound environment can encourage specific outcomes: memory recall, associative visualisation and creative problem solving.

Listening and spatial sound technologies enable us to evolve both our expectations of, and practice with, sound and music culture.

Listening and spatial sound technologies enable us to evolve both our expectations of, and practice with, sound and music culture.

Listening opens up new musical aesthetics.

As we develop new conceptions of space, artists will begin working with new forms of aesthetics in response. We are seeing a shift towards more spatially expansive, materially minimal, durational soundscapes that open up highly refined psychological and emotional states and stimulate a more creative, participative role for the listeners.

Listening needs time and space to emerge.

Accessing the intelligence in listening needs to be cultivated. It requires ongoing practice in the right kind of environment. The more we can build moments of quiet reflection in our busy days, and the more access we have to spaces that encourage reflection and silence, the more our ability to work with listening will deepen and expand.

The virtuous cycle of tuning into the sound of our spaces.

The virtuous cycle of tuning into the sound of our spaces.

Listening helps us create healthier social spaces.

Ultimately, listening can help us create more balance in how we design our shared spaces and how we envision our interactions within them. When our environment is designed to minimise noise pollution and encourage more intelligible communication, we are much more likely to enjoy, and be nourished by, our spaces.

—

Text by John Connell

John Connell is a media strategist, composer and creative director of 4DSOUND, a collective exploring spatial sound as a medium. His sound and curatorial work explores questions of consciousness raised by meditative disciplines and philosophy of mind. A central focus of this is listening as a practice in itself: how our ability to listen opens up new levels of awareness about space, both the external and the internal. He has performed at experimental electronic music showcases such as TodaysArt, Berlin Atonal and the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, with talks and workshops at CTM Berlin, State Festival and Creative Mornings amongst others.

Thanks to 4DSOUND Founder Paul Oomen and research collaborator Robert Jan Liethoff for their input and thinking into this article. Thanks also to Prof. Slobodan Dan Paich, Prof. Andrea Szigetvari and Svetlana Maras for their insightful research.

About 4DSOUND

Building on ten years of research, development and experimentation in spatial sound technology, 4DSOUND opens up new possibilities to create, perform and experience sound spatially. 4DSOUND is a fully omnidirectional sound environment where the listener can experience sound moving infinitely far away or coming intimately close: it moves around, as well as above, beneath, in between or right through you. Led by your ears, you’re encouraged to explore the space. You can move between blocks of sound, touch lines of sound and walk through walls of sound.

In 2015, 4DSOUND founded the Spatial Sound Institute in Budapest, a permanent facility dedicated to research and development in the field of spatial sound and immersive sonic environments.

www.4dsound.net

—

About 4DSOUND

Building on ten years of research, development and experimentation in spatial sound technology, 4DSOUND opens up new possibilities to create, perform and experience sound spatially. 4DSOUND is a fully omnidirectional sound environment where the listener can experience sound moving infinitely far away or coming intimately close: it moves around, as well as above, beneath, in between or right through you. Led by your ears, you’re encouraged to explore the space. You can move between blocks of sound, touch lines of sound and walk through walls of sound.

In 2015, 4DSOUND founded the Spatial Sound Institute in Budapest, a permanent facility dedicated to research and development in the field of spatial sound and immersive sonic environments.

www.4dsound.net

—

Footnotes:

(1) Horowitz, Seth. MD. (2012). The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind. Bloomsbury.

(2) Schafer, R. Murray. (1977). The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Knopf.

(3) Yoko Ono, Grapefruit (Simon & Schuster, 1964).

(4) Prof. S. Errede, Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves (Department of Physics, The University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, Illinois 2005–2010).

(5) Headspace.com

(6) Treasure, Julian. ‘5 Ways to Listen Better’ (https://www.ted.com/talks/julian_treasure_5_ways_to_listen_better)

(7) Mo, Ronald; Choi, Ga Lam; Lee, Chung; Horner, Andrew. The Effects of MP3 Compression on Perceived Emotional Characteristics in Musical Instruments (http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse. cfm?elib=18523)

(8) Golman, Russell; Hagmann, David; Loewenstein, George.“Information Avoidance”. Journal of Economic Literature.

(9) Attention Spans: Consumer Insights Microsoft Canada, available online as pdf

(10) “Digital Hygiene: How we might’ve Fucked our Attention Spans”. YouTube upload by exurbia

(11) “Altering States of Consciousness is a Trillion Dollar Economy: Big Think presents Steven Kotler”

(12) Schumacher, John F. “The Demoralised Mind”. TheInternationalist.com.

(13) Oliveros, Pauline. Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (To Practice Practice). 1999.

(1) Horowitz, Seth. MD. (2012). The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind. Bloomsbury.

(2) Schafer, R. Murray. (1977). The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Knopf.

(3) Yoko Ono, Grapefruit (Simon & Schuster, 1964).

(4) Prof. S. Errede, Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves (Department of Physics, The University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, Illinois 2005–2010).

(5) Headspace.com

(6) Treasure, Julian. ‘5 Ways to Listen Better’ (https://www.ted.com/talks/julian_treasure_5_ways_to_listen_better)

(7) Mo, Ronald; Choi, Ga Lam; Lee, Chung; Horner, Andrew. The Effects of MP3 Compression on Perceived Emotional Characteristics in Musical Instruments (http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse. cfm?elib=18523)

(8) Golman, Russell; Hagmann, David; Loewenstein, George.“Information Avoidance”. Journal of Economic Literature.

(9) Attention Spans: Consumer Insights Microsoft Canada, available online as pdf

(10) “Digital Hygiene: How we might’ve Fucked our Attention Spans”. YouTube upload by exurbia

(11) “Altering States of Consciousness is a Trillion Dollar Economy: Big Think presents Steven Kotler”

(12) Schumacher, John F. “The Demoralised Mind”. TheInternationalist.com.

(13) Oliveros, Pauline. Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (To Practice Practice). 1999.

Related: